In chapter two of Christianity and Literature, Jeffrey and Maillet lament,

“Many literary majors…graduate without any clear sense of whether literary theory enables them to find…any truth, goodness, beauty or even any meaning in literature.”

Because I’m pursuing a doctorate in literary humanities, this statement resonated with me.

If this sort of thing puts your bedbugs to sleep, maybe you’d find this article on Keeping Your Kids Out of Jail more interesting or useful.

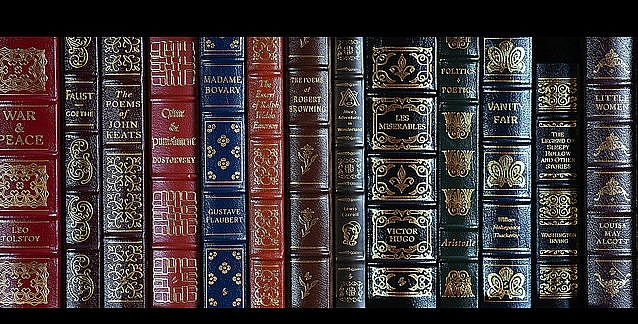

photo credit: Dustin Gaffke

At first, being the nerd that I am, I was tempted to trace the roots of the statement’s suppositions and work out the implications, but I have to concede my understanding of literary criticism is still quite limited and that would be a huge task for a blog post.

Instead, because it is our understanding of truth that can help us find meaning in literature, I decided to explore that most fundamental aspect of literary theory.

If you’re a writer or a teacher, hopefully, you will find some value in this brief summary of the three theories of truth as presented in Christianity and Literature.

The first theory is what is called correspondence theory.

Correspondence theory can be understood as “a verbal claim being true only if it corresponds to pertinent fact or external reality.” Put another way, it is only true if it is true, literally. In order for a truth claim to be valid under this theory, it must be demonstrable or observable.

For example, if one claimed the extravagant sports car he recently started driving, in fact, belonged to him, he would only need to produce the title to verify his claim. Two other aspects are important to note.

First, as Jeffrey and Maillet assert, “a valid correspondence is likewise objective and mind independent.” This means truth is not subject to our taste or appreciation of it. Actual truth in this theory does not need anyone’s approval to be true; it just is whether it is recognized or not. For you nerds out there, another term for this is philosophical realism.

And second, correspondence theory does not exclude faith rightly attributed. Just a like a scientist relies on the experiments and records of previous studies performed by reputable scientists, by faith, so Christians are not wrong to “accept as reliable the knowledge tradition of the church and ultimately of Scripture itself.”

There is also “a kind of truth that pertains less to physical realities or events than to a set of propositions within which a claim may be regarded as true if found to be logically consistent—or coherent—with the rest of the data set.”

This is called coherence theory.

“Coherence truth involves a criterion of appropriate relationship of reasonableness given certain presuppositions.”

Examples given in the text are that of chess, where there is not any real correspondence between the game and the reality of its “medieval counter-parts,” and writing, where the writer is able to create imaginary universes analogous to but different from our own.

In both cases, when the fictitious worlds are self-consistent with their predetermined domains, they are said to be true, even if they do not “actually” correspond to pertinent fact.

The third truth theory, called pragmatic theory, “dominates literary theory in our day more than any other.”

In pragmatic theory, truth is always relative and subjective to the individual perceiving it. In this theory, something is held to be valid if it works, and often changes and morphs when the consensus of the community does. It’s sometimes perceived as just common sense.

As one might quickly intuit, unlike correspondence and coherence theory, there is no room for pragmatic theory in Christian literary theory. And one of the essential aspects of literary theory—particularly for the Christian—is discerning under which truth theory the writer is operating.

As I examine the theories previously discussed, I would affirm the belief that Christians can find meaning in literature if they read it with a critical eye for truth.

By virtue of its form, literature creates an alternate reality with analogous contexts that shape our perception of the real world. Concern for the truth then, though “disguised as a fable, parable, or ‘harmless tale,’” becomes the Christian critic’s passion. When we read with our eyes open, we will see elements that are true in our own life and world.

For example, in the Greek tragedies, by way of the sufferings, fear and pity are aroused in the audience, effecting catharsis, which means their souls are “lightened and delighted” for having experienced the tragic fall of the character.

In reading literature, Christians ought to “readily see lived reality beneath an engaging cortex of imaginative analogy and say… ‘Aha! That rings true.’”

Bibliography

Jeffrey, David L., and Gregory Maillet. Christianity and Literature: Philosophical Foundations and Critical Practice. Downers Grove, Ill.: IVP Academic, 2011.

Richter, David H. The Critical Tradition: Classic Texts and Contemporary Trends. 3rd ed. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2007.